Slow Read: Week 10

Art of the Everyday

Resisting the Too-Easy Story

In Chapter 9 we return again to the everyday. But this time, rather than focusing on the delights of the mundane, I ask us to make room for complexity. Sometimes seemingly straightforward scenes of ordinary life can conceal the real complexities of a history or relationship. At other times, representations of the everyday can add complicating texture to those who have been stereotyped or flattened by other cultural narratives.

Scenes of everyday life appear in Egyptian tombs and medieval manuscripts. But it was in seventeenth-century Holland that genre painting came into its own in the west. Dutch artists depicted peasants, revelers, raucous family gatherings, women working at home, and even dentists performing extractions!

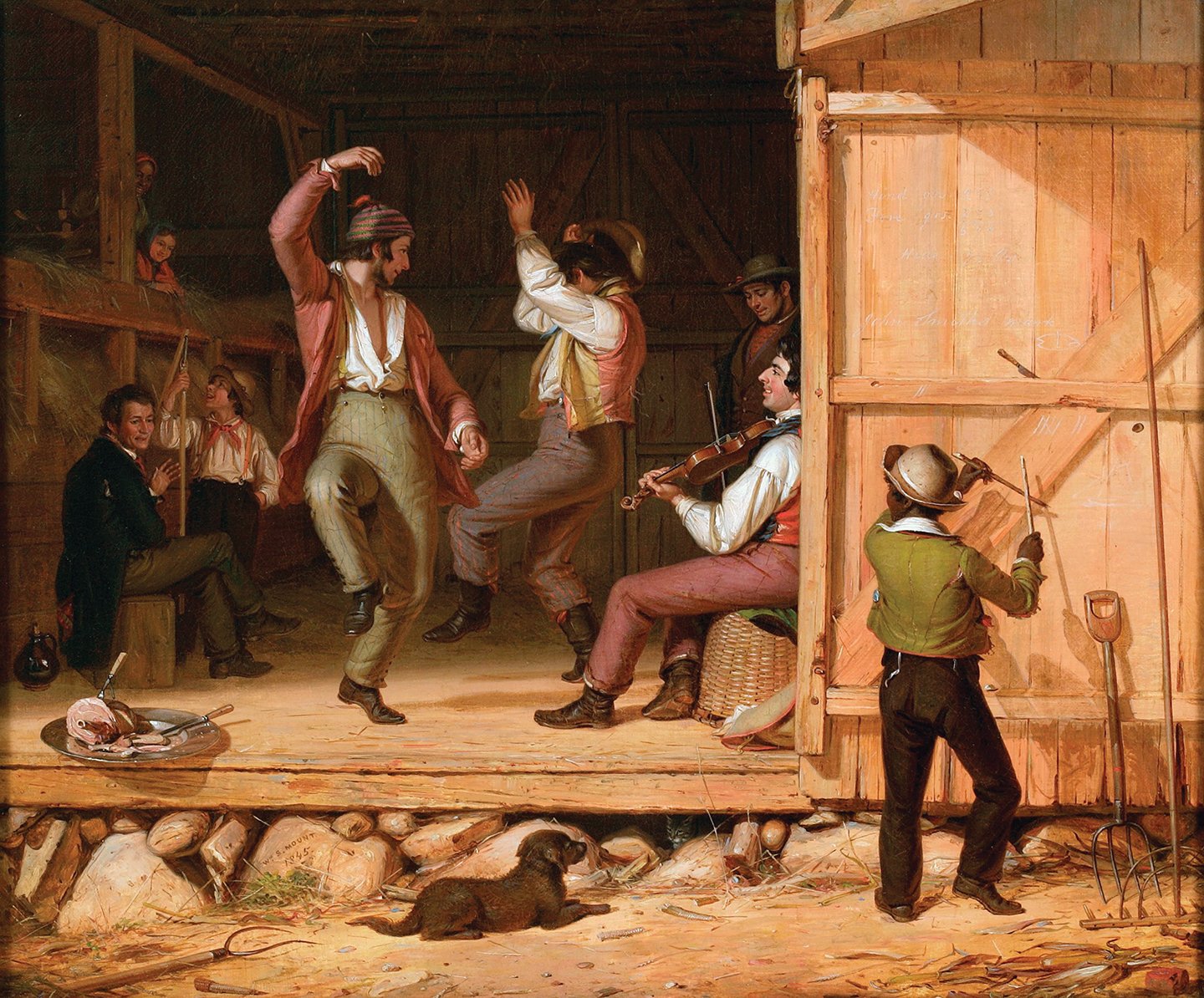

In the United States, genre painting played an important role in shaping the national imagination in the nineteenth century. The antebellum period was one of immense cultural anxiety. Older social hierarchies and norms were being challenged, and the threat of national collapse over the issue of slavery loomed large. Genre painting provided a means of visually stabilizing American identity.

While white Protestant viewers’ lived experience might feel precarious or complicated, genre paintings told a simpler, easier story that was comforting, charming, and often a little funny.

I knew I wanted to write about a William Sidney Mount painting for this chapter. Mount was a New York-based 19th century American genre painter, and he included African Americans in many of his paintings. Most of his figures are painted without exaggerated facial features or overt stereotyping. But, there is another consistent thread that should give us pause. (You can click the image to see them larger at their institutions’ websites.)

Can you see it? You’ll read more about it in the chapter.

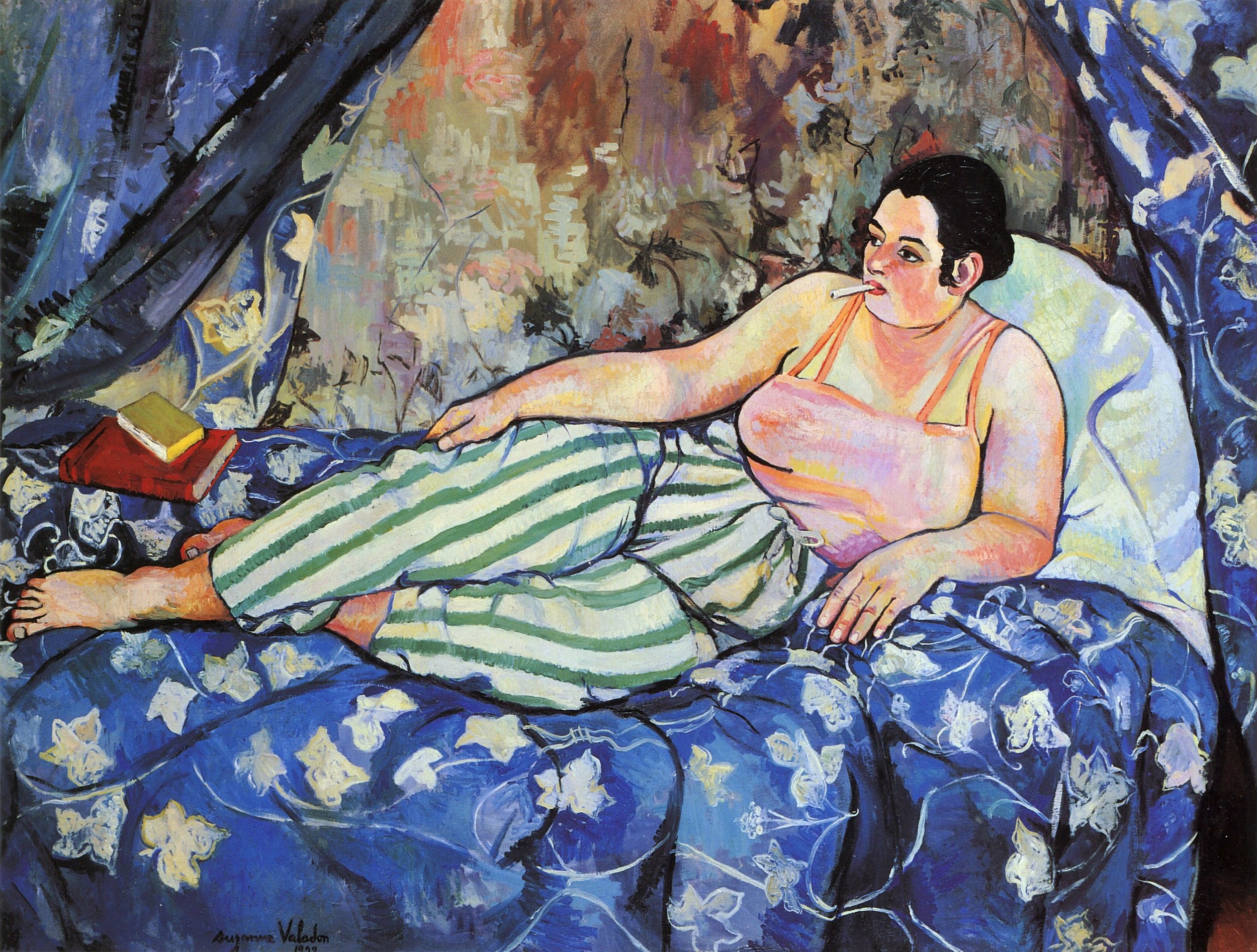

And then we have Suzanne Valadon’s Blue Room. Here, an everyday scene helps us question a type of image that we might otherwise take for granted. Basically, I wanted to write about the powerful trope of the reclining female nude in western art history without having to actually show a reclining female nude. I certainly teach a lot about those artworks in my classes, and I list a brief history of them in the chapter. But here I wanted to create a productive friction with the images that likely already live in your archive.

Side note: if you found the incredibly truncated history of the nude female body in art compelling and distressing, let me know. I would love the opportunity to write more about the visual stories—like that of the available, vulnerable Venus—that have shaped women’s lives in the West.

Suzanne Valadon’s life story is certainly compelling: a working class girl modeling for painters in Paris’s bohemian district then learns how to paint herself. She’s all sweet charm in Renoir’s painting of her at an outdoor dance:

And then in Puvis de Chavannes’s painting, she serves as the model for all the elegant, classicized figures. But the discrepancy between the life Valadon portrayed as a model and her actual experience really stood out to me as I wrote the chapter.

Even though Valadon and other women posed as Venus, they were hardly treated as goddesses. Although the paintings were lauded as cultural treasures, the women who modeled for them were assumed to be women of low morals. By making their bodies available to the male artist’s gaze, models were assumed to also make themselves sexually available.

Valadon does paint a number of nudes in her own artistic career, but as in The Blue Room, the bodies she depicts are boldly outlined and often situated in naturalistic—sometimes even awkward—positions. She paints women who live in their bodies, not bodies that represent an ideal of womanhood.

In re-reading this chapter, I’m pleased that I honored the complexity of Mount and Valadon as people themselves. Mount is not a simple racist villain. Valadon is not a proto-feminist heroine. And that’s the hope, right? That as artworks teach us to make space for complexity we can extend that expansive grace to our historical and current neighbors, too. Maybe we can even do that for ourselves.