Slow Read: Week 11

The Art of History

On History and Art that Makes Me Cry

Was I plotting this chapter from the moment I drafted my book proposal? Yes, yes, I was. Chapters 10 and 11 are in many ways the heartbeat of this book; they exemplify why I’ve dedicated my life to teaching art history.

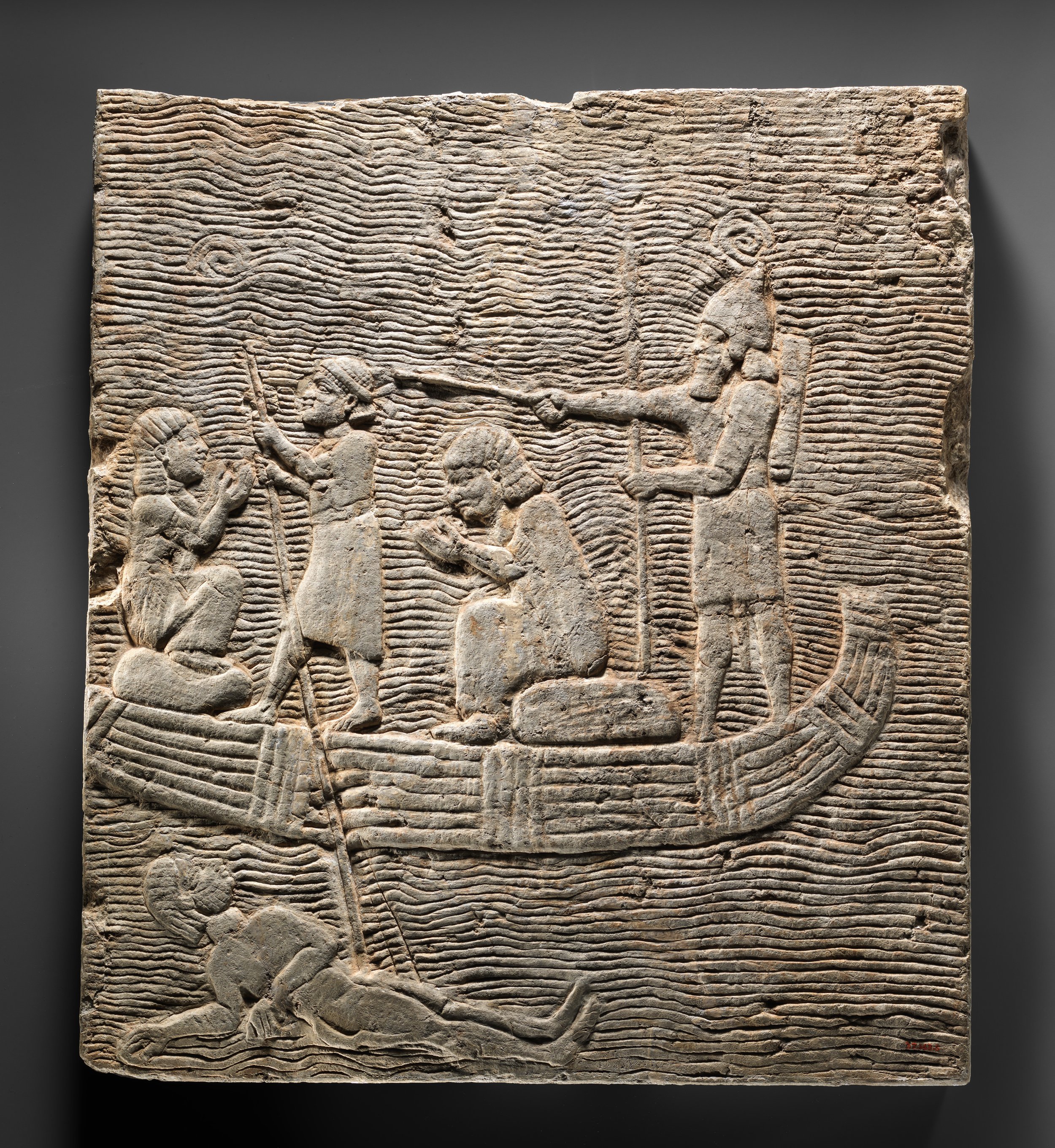

Images shape our imagination; they teach us how to tell stories about our past and our present. Often, images that represent conflict rely on visual contrast to set up a moral contrast. Chapter 10 begins with an Assyrian relief carving and an 18th century print from the beginning of the American Revolution. Though they were made thousands of years apart, both of them use contrast—in shape and color or texture—to clearly and unequivocally divide the depicted figures into two distinct camps. And these aren’t outliers in our visual culture. The Early Dynastic Egyptian Palette of Narmer, Francisco Goya’s Third of May, 1808 from 1814, and even the epic ending battle scene of Avengers: End Game all do the same.

In the chapter, I also compare Paul Revere’s Boston Massacre print to the later propaganda images of World War II. Propaganda posters often dehumanized the enemy, literally turning German or Japanese leaders and troops into shadowy looming figures or unsavory animals like snakes or rats. Revere’s print suggests that the redcoats are a monolithic killing machine, the opposite of the highly individualized colonists they are attacking.

Beyond just visual similarities, Revere’s print also shares a similar goal with World War II propaganda. These images are not primarily interested in a documentary accounting of actual events. Instead, they serve as a means of creating social cohesion. They help us understand who we are by neatly defining us in opposition to someone else. The print does not ask us to reflect; it wants us to react.

While it may be an efficient way to mobilize for a cause, Revere’s approach does us a historical disservice. After all, history is not just what happened in the past. It’s how we tell the story of the past.

Revere naturalizes a single point of view with assumed distance and clarity. His way of telling is authoritative. But his simplification of events is also a distortion. And this distortion creates false moral stakes. If we acknowledge—let alone express sympathy for—the lone British soldier who was pelted by snowballs, sticks, and verbal abuse prior to this confrontation, then Revere implicitly pegs us as equally heartless as the chilling row of red coats.

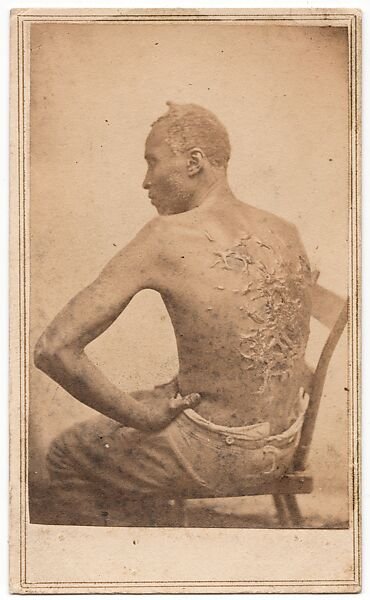

And this brings me to the final case study in the chapter, and one of my favorite works of art: Carrie Mae Weems’s From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried. As a historian who tends to cry a lot over what I’m studying, Weems’s photo-text installation resonates on many levels. Especially since I started teaching histories of photography, I’ve been very taken by the notion that artists can “do history” with their work. Like historians, artists can make use of archives, interpreting primary sources to narrate the past in ways that help us understand our present better.

Weems also challenges some of the practices of history-telling that Revere (and others) use. Instead of presuming to have complete, objective knowledge, Weems calls attention to absences in our historical archives. Instead of casting one group as villain and another as hero, Weems acknowledges the complexity and agency of all involved. She even allows for contradiction. And finally, instead of telling history as a form of celebration or self-righteousness, Weems invites lament.

Weeping may seem like a strange or even anti-intellectual response to art and historical narrative. And yet, this is the appropriate response to injustice modeled for us in Scripture. Scholar Claus Westermann has argued for the primacy of lament in the Old Testament as a means of giving voice to oppression, anxiety, pain, and peril and appealing to God’s compassion. We see lament offered throughout the Old Testament as a means of the people of Israel, corporately and individually, expressing outrage and sorrow over affliction past and present.

Lament in the Judeo-Christian context is also a declaration of relationship. When the people of Israel publicly mourn the violence they’ve experienced, their grief is an expression of faith in a God who promises to be with them. They know their sorrow will be carried. They know that restoration will eventually come to pass, even if they might not understand precisely what form that will take.

When I first drafted this chapter in November of 2021, I could not have foretold the agony and bloodshed currently taking place in Israel and Gaza. But I wrote this:

“When we look at artworks that tell histories or see photographs of recent, dramatic events, we should ask ourselves who we are tempted to dismiss or even hate. Who are the bad guys, and how do we know that, visually? And remember, an artist can also shape our perception of a person or group of people by not representing them at all. This is not to say that we should excuse violence or fail to acknowledge the disproportionate use of force. But when our enemy is set up as utterly foreign to us, it is far too easy to forget that they, too, bear the image of God.”

May God give us eyes to see and voices to lament.

We’re nearing the end, friends! Next week is our final chapter!